Shakespeare Central Times Interview:

David Cope is a long time teacher of poetry, Shakespeare and literature. He is also the Poet Laureate of Grand Rapids, Michigan. Steve Rowland interviews David Cope via E-mail.

Dave, very nice to ‘meet’ you and to be connected with you. Thank you for agreeing to be the very first in a series of interviews with writers, actors, directors, scholars, educators, students, prisoners, and even politicians for our new on-line journal The Shakespeare Central Times.

We are very interested in learning about and talking about the ways that poetry, literature and drama operate in today’s world – the ways in which engagement with these arts can enrich us and bring people closer together. And understanding the present often requires understanding the past and the path we have collectively taken to get where we are.

For us at Shakespeare Central, Shakespeare plays a critical role in this understanding – the world he lived in, and the importance of words in his world; the journey the plays have taken over the past 400 years, the reverence for his works now, and perhaps most importantly, how these works can be used as the basis of a continuing global dialogue in years to come.

1. What is your relationship with words? Why are words important to you? (alternatively, how do you view America’s relationship with words?)

Words are a source of endless pleasure to me, in a great variety of ways: in oral recitation of poems ranging from the opening lines of the Old English Eard-Stapa (Earth Stepper, The Wanderer) through Chaucer’s “Whan that Aprille with his shoures soote / the droughte of March hath perced to the roote”—and of course the great pleasures of Shakespeare’s oral poetry and the exquisite Italian of Dante, among others.

They’ve also been a means to define or clarify life situations and my own feelings about things that trouble me—whenever I felt my life was falling apart, words were the means to understand myself and the situation itself. As a poet, that kind of defining clarity has given me the method and means to track my own journey through life and out of it, ultimately, but it has also helped find key passages in the life of our nation during my time on earth, the beauties of our landscapes and waters, the struggles of our people during war years, recessions, etc.

Sometimes, they’re simply the tools one employs when trying to understand something important. When I retired from teaching, I found I had time to catch up on my love of Dante. Shakespeare, Whitman, Williams and contemporary poetry had consumed my life during my teaching years, and while I dove deeply into the Commedia in my graduate work, I had to leave it until now. My first project of retirement (or, of my new life as I prefer to call it) has involved my long-delayed Dante Project, beginning with a timeline of his life contextualized with Florentine historical events that give his life the context in which he lived, and building a list of important criticism, biographies, etc. over the long centuries his work has been with us—from 1321-2013. A second project involves the editing of my book, The Invisible Keys: New and Selected Poems, and going through the process of submitting that book to publishers—the “business” of writing.

I tend to write a lot of letters and emails, too, keeping up with friends, answering queries, etc. I love words, to be plain—at this point, they’re so bound up with the fabric of my life that I can’t really separate them from it.

America’s relationship with words is a much more complex question, ranging from the corporate takeovers of publishers and the snap judgments of social media to the Supreme Court’s “Citizens United” decision, which defines self-expression in terms of the right to buy elections through the worst kind of political half-truths and outright lies to fool the populace into voting for a rich man’s agenda. I think we are living through a period in which language itself is being mightily abused by politicians, corporate interests, racists and homophobes.

On the other hand, while poetry is not as highly valued/subversive as it was when I was growing up, we are going through a period when filmic masterpieces appear with regularity—whether in the superb scripts and performances of Lincoln or Twelve Years a Slave, or in the dark comedy of Budapest Hotel or the sublime editing and performances of The Hollow Crown, the recreation of Shakespeare’s major tetralogy (Richard II, I and II Henry IV, and Henry V). This last features not only legendary elders but also a bright new generation of actors full of promise—Tom Hiddleston, Ben Whishaw, Michelle Dockery, Patterson Joseph, Rory Kinnear, and others.

2.) What is your take on the relationship people had with words during Shakespeare’s lifetime? How was he able to write in a way that people of various classes all understood the plays?

Shakespeare lived in a “totalizing society” (as noted by Stephen Greenblatt) in which authors had to be wary of offending the royals, the nobles, even the Spanish ambassador. The Master of Revels—an official court censor—had to OK a play’s script before it could be performed, and the effects of his displeasure could be frightening—Ben Jonson was famously in hot water for his Sejanus, a play which may have obliquely glanced at the Essex rebellion or the trial of Raleigh; Shakespeare himself had to change the name of the Puritan martyr Sir John Oldcastle to Falstaff because of a complaint from Lord Cobham, Oldcastle’s descendant. More famously, those involved in the 1601 Essex rebellion had asked Shakespeare’s company to play Richard II with the deposition scene, on the night before their attempt to kill Queen Elizabeth, and the players had to answer for it

(see my Shakespeare Project, Course Notes #1, pages 31-32: http://cms.grcc.edu/sites/default/files/docs/shakespeare/course/shakespeare_course_handouts_cues_1599.pdf ).

The poets of that time lived in a rapidly expanding universe, despite the tight government control of what could be treated directly—and that expansion included language. I think it’d be difficult for the audiences to grasp all the subtleties and nuances of the poets’ language, but everyone could make sense of what a play did, given that the words were aided by actors playing them with feeling, as we can see at the London Globe or other theatres even today.

The language is initially foreign to a lot of Americans, but going to a show or a film, or speaking the words aloud in a classroom can make these things come alive. It does take time and effort, especially given his enormous vocabulary and latinate sentence structures.

As for the social class question, actors understood (and understand) that many of the Elizabethan playwrights knew how to play to the commoners—the groundlings—as surely as to the nobles. Characters like Shakespeare’s Falstaff, Middleton and Dekker’s Moll Cutpurse, or Jonson’s Volpone all bring subversive voices which at once challenge the assumptions of the upper classes and yet find themselves contained by play’s end—giving a voice to those who “have not.” It was, after all, public entertainment which featured the stories that people found enthralling, as with a good film or TV show, but also included dances, the music of the period, the enactment of famous battles and the presentation of important historical figures, too, as seen by their own contemporary writers.

3. Do you think of poetry mostly as a written art form or a spoken, oral, art form? And, how do you think we should engage with Shakespeare – from the page or aurally?

A poem is a script to be read aloud, and if the poet is careful, a good poem gives the reader cues as to how it could be performed—whether through pauses at line ends or in the phrasings and metrics of the syllables, as well as their musical qualities. Readers never know a damned thing about a poem if they’re reading silently—it comes alive in your mouth, when you practice it and learn how to “say it” with some feeling for what it does.

As a Shakespeare professor, I spent a little time going over important arguments about the text, contextualizing it, and then we dove into reading key passages aloud. I took the larger or more difficult parts because I already knew them, and students would grab others. It was sometimes a brilliant discovery of our own reading skills, and other times a groping along when some readers weren’t particularly gifted—but I was patient and gave everyone their shot at it. If we got to a particularly tough passage, we’d stop and I’d ask them to try to make sense of it, usually leading to a discussion of what it “did.” I was particularly attuned to doing plays that had strong women characters so that both male and female students could be a part. Looking back, these were my happiest hours as a teacher—and I was lucky enough to attract some of the most gifted students at the college, so it was a time of growth for us all.

I do think the lecture approach is sure to put students asleep, and that silly “reading quiz” approach taken by some teachers is merely insulting to students. Invite them to read the text in advance, answer any questions they pose on email before class, and plunge into the play with them—doing it with gusto—and sooner or later, they’ll find themselves having a ball with it, and learning too.

4. How important has it been to you to be a teacher? what have you learned — about people, about writing? how has being a teacher changed you and your writing?

I have always been, first and foremost, a poet. This was my life choice very early on, and everything else has been built around my writing. On the other hand, I come from people who, when they take on a task, give everything they have to it—thorough, persistent, stopping at nothing to get to the very bottom of a task or a subject. I first fell in love with Shakespeare in 10th grade and Dante in 11th grade, reading the Commedia while home with pneumonia in the dead of winter, the Rolling Stones shaking it up in the background. Chaucer came to me as a senior, where I memorized the first 35 lines of the Prologue and recited them in class, imbuing them with a slightly French twist in my accent—I reasoned that Chaucer’s English was a layering of Norman French over the Anglo-Saxon base. Later, at the University of Michigan, my Shakespeare studies came at the same time as poetry writing classes with the famed poet Robert Hayden—so my literary studies coincided deeply with my developing skills as a poet. This has been a lifelong thing, and when I finally reached the point where I could teach, I brought those deep loves with me, and gave these poets everything I had in my teaching.

Teaching does involve deep learning about human nature, and because it involves an enormous amount of research and writing—if done properly—it can help hone one’s ability to express oneself. I had an average of 150 students each semester (6 or 7 classes, depending on the circumstances of my life in a given semester—I was also raising my 3 kids and pursuing my poetry career at the same time). With a load like that, one has to zero in on students and understand their needs—the goal being to help them learn what they need to succeed and, with a little luck, to understand themselves a little better. Of course there were stinkers among them, but I tried to be patient. The beauty is that my finest students have all friended me on my Facebook page, and our conversations continue to this day.

So teaching did a lot to change me, and the research required to be a good teacher has helped me hone my skills as a writer. Still, if one looks at the books I wrote while serving as a custodian, there was an immediacy and close observation of plan folks and their lives which is a bit different from the poems which came along once I entered that high-power world of college professorship. I’ve tried to keep that awareness, that compassion, alive in the later poems, too—though I’d be first to admit that the eloquence is sometimes of a different order, though no less effective. Of course, I never wanted to repeat myself—each book should be a form of growth and change.

5. You have a wonderful connection to poetry and writing of many eras. Please tell us a little about your connection to Allen Ginsberg. Also, please tell us why Ginsberg is such an important artist.

This story starts around 10th grade, when a friend and I hitch-hiked downtown to the one bookstore that would have had their works. I was one angry young man—my father had walked out on the family a few years before, and by 10th grade I was a seething punk with a huge chip on my shoulder. I was “starving, hysterical, naked” and Allen’s Howl gave me the OK to feel my feelings, to go nuts at a time when teachers wanted me in detention, family members tried to soothe my feelings away, and my therapist tried to be a “buddy” when he frankly creeped me out. Howl gave me that assurance that madness sometimes happens to the best of us, but it also reminded me that my life was holy, was worth living—in Blake’s words, “everything that lives is holy.”

Later, when so many in my generation were enmeshed in the depths of rage and depression over the Vietnam War, dead friends, police riots, a nation become alien to us all, Allen came to Hill Auditorium in Ann Arbor and recited his poems to us on Moratorium Day, November 1969. So many in that audience of 3500 felt their tears and let go that day, relieved to share our sorrows in that dark time. Four years after that, when we were exhausted by our protests, struggling to make sense of our lives and looking for a different way, Allen, Ken Rexroth, Robert Duncan, and the objectivist masters—Charles Reznikoff, George Oppen and Carl Rakosi—came to the National Poetry Festival in Allendale. Here I got my first real introduction to the man, his compassion, and the kinds of relationships real poets have with each other—their friendships, camaraderie, the intense dialogues ranging from personal relationship issues to a deeper understanding of poetics, to questions of international politics.

My wife Sue and I spent time with George and Mary Oppen, who accompanied us to the midsummer bonfire, and while youthful writers and their aged counterparts danced like so many satyrs around the bonfire, the Oppens regaled us with the tale of how they ran away to France as a very young married couple, telling the tale of peasant bonfires in the hills on crisp autumn nights. I also managed to get Allen’s address before the conference was over.

My journey back to my father—to forgiveness, to loving each other and sharing our lives—took over 10 years, but it would never have happened without Allen’s validation in Howl and later advice that I would never be free until I let go of my own anger toward him.

A year after that, I began publishing my Big Scream poetry magazine, and by 1975, I sent Allen a copy of my first chapbook, Stars. He wrote back, all excited because it reminded him of Reznikoff’s style of objectivism (I had taken Charles’s style and the many experiments of William Carlos Williams to heart and was working to develop my own vision in the same lineage). Allen sent me a check and ordered 10 more copies of the chapbook, and later was instrumental in helping me win a Pushcart Prize in 1977, also editing some of my work for New Directions Anthology #37 and City Lights Journal #4. He believed in my work, and had me come out to Naropa Institute (now University) in 1980, to meet my peers, read my poems, and teach a seminar in Reznikoff’s poetry. Later, when my first book was to be published in 1983, Allen wrote the foreword.

Our friendship lasted the rest of his life. We read together on occasion and he was on the committee that chose my On the Bridge for the 1988 American Academy/Institute of Arts and Letters literature award; I was instrumental in developing the 1990 Ecopoetics Conference and the 1994 Beats and Rebel Angels Conference at Naropa, and when he needed funds to get his teeth fixed, I arranged a reading for him at my college, GRCC. Finally, I was among the last of his many friends that he called when he was dying—to say goodbye.

Allen wasn’t a major influence on the style of my poetry, though I shared his demand for honesty, intense ordinary speech, and precision in craftsmanship. He taught me compassion, a pull-no-punches honesty, caring for one’s writing peers intellectually and emotionally, economically if necessary, and he taught me how to tie my tie. There are so many other stories that could be added to what I’ve written here—but these are the lineaments of one of the most important relationships in my life.

6. Tell us a little about the importance of the Beat movement and its connection to American life. Some people describe it as a kind of antidote to the deadly conformity of Post War America, do you? If so, how do you explain the deadly conformity we suffer now?

The Beats were the first to kick down the door of what the Who later called the “frozen storm”—the horrors of an angry McCarthyism that saw Communists under every rug, the us vs. them mentality that infected international politics, and a sexual and social puritanism that made youth afraid of their own awakening love interests. Conformity is always a problem in each new generation or movement, and the Beats certainly broke down much of the “grey suit” mentality of the age. Today’s conformity involves a generation enslaved by technological machines—video games, social media, “smart” phones, etc.—incapable of seeing the real world beyond the latest techie craze. No poets rising to speak for them, rock stars whose idea of revolution is changing their clothing to something more “outrageous” than last year’s model. Children crying real tears about their shrunken social and job possibilities, the horrors of lifelong debt for college careers that left them unemployed. The prospect of an earth headed toward ecological apocalypse always on their horizon, along with the endless parade of mass shootings in schools, malls, on the streets. One tends to think less of standing out as a non-conformist, more about simple survival and retreating into fantasy, in such a scenario. I see it as very sad—and I must say, it’s the Shakespeares and the Whitmans, the Beats and the Dantes who can give them access to real feeling, along with entering the wilderness and hearing their own hearts unclogged with technological terror.

7. Do you see Ginsberg and his contemporaries as having a direct connection to Shakespeare or do you see these writings as existing in different realms altogether?

Allen sometimes taught The Tempest in the summer sessions. He loved the poetry of that play and especially the themes of giving mercy to those late-repentant, and the personal buddha-like theme of letting go, “like this insubstantial pageant faded,” leaving “not a rack behind” with the goal of retiring “to my Milan, where every third thought shall be my death.” In his 1977 poem “What’s Dead,” Allen makes a litany of the famed dead, including “Shakespeare the Magician” among his “musings of Buddhist student Allen Ginsberg,” and in his famous “Ode to Failure,” he notes that “Prospero burned his Power books & plummeted his magic wand to the bottom of dragon seas.” In all, there are seven references—including the line with Prospero—to Shakespeare as a cultural touchstone, the “magician” who gave it up, let it all go in the end.

He was also quite fond of the sonnets; his early poems show a decided Elizabethan influence at times, and while he loved the period and its greatest authors, he was a mental traveler, always on the lookout for new voices, enjoying the wisdom and foolishness of his peers. He had special feeling for Walt Whitman, William Carlos Williams, and Charles Reznikoff, but his work overall shows an appreciation for a wide variety of styles and approaches to verse—the gallimaufry, as he once called it in the notes to his First Blues album.

As for the question of these writings existing in different realms, the worlds of beat poetry and Shakespeare are in some ways quite far apart—multi-voiced dramatic poetry enacted via collaborative labors on the part of directors and actors vs. that lone voice (or that lone voice backed by jazz or experimental musicians) in very different cultures and time periods. Still, any poet needs to learn his or her chops, and the tool kit of technique and eloquence begins with Shakespeare, Dante, and for Americans, Whitman and Williams, among many others. The great ones of the past had the same task as we do today, in any case—to tell their story, and the stories of their time, as truly as one can. Without that long knowledge of the art growing and changing through time, the younger artist—poet, musician, painter, script writer or filmic genius—has little grasp of the real possibilities—what has been done and is still available to be made new.

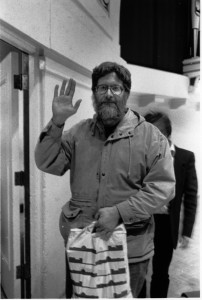

Dave Cope hiking with fellow poet Tom Schwartz, during visit to Jack Kerouac Conference at the Naropa Institute.

8. How do you view the relationship of contemporary poetry with contemporary life – -connections to political movements, social movements? Often the ‘public’ ignores poetry and feels that it is something relegated only to academics. Yet many poets feel deeply connected to social movements and want their work to be relevant to people from a wide variety of race and class backgrounds. How do you view this dichotomy?

Michael Rothenberg’s 100,000 Poets for Change (http://100tpc.org/ ) is a major international movement of poets protesting for a better world, and poets across the nation read and share poems that go directly to public, social issues in readings and indie magazines. Poetry has usually been an “outsider” kind of art, and though there are times when poets arise who have the moxie to break through the veil of sleepy discontent, end time anxiety, and excessive concern with the “self” and “self-image” that are the perpetual themes of news, shows, and commercials, it is more and more difficult to do so. Anne Waldman once warned that we are entering the age of the Kali Yuga, and it may be that the poets’ task in such darkness is to preserve the moisopholon domos (the house of the muses) and keep the light there until a better time may arrive. I think it’s important to record the private lives and great events of our time; every poet—in any age—writes as though looking back at his or her own time through the eyes of the dead, as in the faces on the walls of Pompeii looking back at those of us from later times as if to say, “I too was like you. I lived and loved, and my people mattered in the great scheme of things. Live and learn.”

9. In teaching Shakespeare how much should it be treated as literature which is read silently, and how much should it be treated as text to read and hear out loud?

Read aloud whenever possible; go to see it performed in theatre or on film whenever possible. It lives in the voices and actions of the actors, and can come alive in a shared reading wherever committed people take parts and read with gusto.

10. What advice can you give to young teachers who want to teach Shakespeare?

Read aloud with your students, taking parts. Don’t be afraid to make an ass of yourself—we all wear donkey ears at one time or another, and these “teachable moments” can be times to laugh and grow together.

Be patient with your students’ struggles and questions, and if you don’t have an answer for a student’s question, help yourself and the student find one. Engage them both in class and via email dialogues. We all learn together.

Don’t stick with the same plays—change it around every year or every semester so that you can eventually teach the whole catalogue with authority; it’s a lifetime’s commitment.

Be aware of current scholarly trends and be able to share that knowledge with students curious about issues similar to those trends.

Writing assignments should be challenging to them, but if you work with them as they develop their ideas, they’ll often surprise you with the complexity of their understanding. Give them a good writing primer and MLA documentation for Shakespeare essays, too. See: http://cms.grcc.edu/sites/default/files/docs/shakespeare/course/writing_academic_essay_en252.pdf

Be willing to take chances—during my last two years of teaching, I taught a “Shakespeare Goes to the Movies” class wherein we read a play and then saw how a film reinterpreted it. There are many kinds of Shakespearean adaptations, and the students and I would investigate four such approaches with each 6 week class (4 plays, 4 films). For more info on that, see: http://cms.grcc.edu/sites/default/files/docs/shakespeare/contemporary/shakespearefilmprimer.pdf .

11. Have you observed changes in the general way in which Shakespeare is both perceived and taught from, say, the time you began teaching?

Yes, I suppose—in the early 90s, there was a move by administrative types to try and realign English Departments away from literature and complex discussion to a kind of utilitarian approach to language—in the words of one Dr. Daggett, “throw Shakespeare out the window and teach students to write better VCR manuals.” That approach to teaching English has remained throughout the past 25 years or so—and anyone who values the history and complexities of our language, the beauties and challenges of its master writers, especially of Shakespeare, should be on guard against this kind of commodification and dumbing down of the word.

In the scholarship, there have been major sea changes in approaches to the bard from the time when I was a student in the 1960s. Back then, we learned the texts via the “new criticism” which insisted that there could only be one correct meaning to the plays, and that historical and cultural details were largely extraneous to understanding the plots and characters—meaning was only to be found in the words themselves.

Feminist criticism came along with Juliet Dusinberre’s Shakespeare and the Nature of Women in 1975, and while she took an enormous amount of criticism from her male counterparts, she set a revolution in motion. As a returning grad student in the early 90s (I was teaching 19 hours of classes at CC and going to grad school at the same time), I had just developed one of the first multicultural literature classes on the western side of our state, and wanted to approach Shakespeare’s plays from the standpoint of their marginalized characters, the women characters, simultaneously exploring the historical and cultural backgrounds implicit in the plays. My first large essay, “Barabas and Shylock,” explored not only the arguments about the representation of these two Jewish characters in plays by Marlowe and Shakespeare, but also the long history of anti-semitism in England and Europe over 1600 years, as well as the ways in which Jews were shown in English literature before Shakespeare. I was lucky enough to win the university’s annual graduate level Shakespeare prize for this essay, and found that employing cultural criticism, Afrocentric criticism, deconstruction, semiotics, and most especially feminist criticism helped me discover new ways to appreciate the complexities of the bard. Link: http://cms.grcc.edu/sites/default/files/docs/shakespeare/contemporary/barabas_and_shylock.pdf

These approaches dominated criticism and classroom discussions across the nation for most of the decade, and yet there have been many changes since. Feminist critics such as Coppélia Kahn have turned from questions of how a woman is characterized and what options are open to her, to questions of how patriarchy damages men, as in the Roman plays or in Troilus and Cressida, where men live by a code of emotional silence, emulation and one-upmanship, blind to their own predicaments and unwilling to listen to women who love them and who can see what is happening to them in the male world of power politics. The other major development in recent years has been the growth of a fairly complex group of critics exploring the many ways that film can rethink a play, ranging from the cross-cultural plot adaptations of Kurosawa’s Ran to the play-within-play approach taken by Kiss Me, Kate or Shakespeare in Love, to the stripped-down “movie” approach which typically uses about 40-60% of the script and is set in landscapes and costumes reminiscent of the times.

So, lots of changes, all of which remind one that this author is so much more complex and “elastic” than any of us could have imagined when we first fell in love with him. As with Dante or Whitman, his work is the study of a lifetime.

12. Bonus question: Asked on behalf of my 21 year old daughter, Mariel, who is currently studying in Santiago, Chile and wondering why young people there are so much more socially conscious than her contemporaries here in the US. One gets the sense that poetry is more deeply entrenched as part of modern day life in Chile (and other countries) than it is here. Do you agree? and do you think that this acceptance might lead people to generally be more socially and politically engaged, or even to be more in touch with the startling everyday beauty of life?

It seems that poets are much more revered in nations where oppression is naked and honesty is actively discouraged. Yevtushenko, when he visited here, spoke of how poets are cultural heroes in Russia because they have traditionally been the ones who have refused to be silent when a dissenting voice is needed. Chile, of course, has a magnificent model of the cultural hero and master poet in Pablo Neruda, perhaps the greatest poet of the 20th Century; poetry that shows the kinds of social and political engagement as he practiced does give a model for social consciousness on the part of young people. Allen had that effect, too, as in his and Dick Gregory’s leading of young protestors away from the Grant Park police riot at the 1968 Chicago Democratic Convention—saving them from tear gas, beatings, the madness of our national obsession with war and militarism. Those who are committed to poetry tend to be more sensitive to the horrors done to those who have nothing, and to the possibilities of love and compassion, but there are also some who are very much self-obsessed. It is like any spiritual path—loaded with possible wisdom, but dangerous to one who does not know him or herself well. Long journey to awareness!

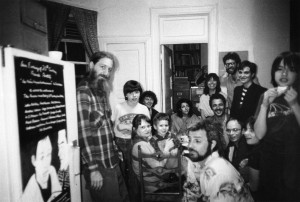

The Friction “Obscure Genius” photo was taken by Allen Ginsberg in his kitchen–including Andy Clausen in foreground, Antler (long beard) and Dave Cope (between two women), as well as poets James Ruggia, Bob Rixon, Nina Zivancevic and others. This photo later appeared on the cover of Friction 5/6, an issue edited by Randy Roark and Allen.

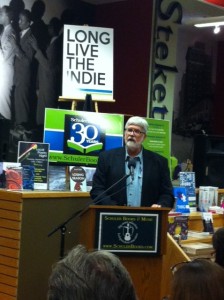

2014- David Cope with Steve Rowland – please share far and wide – and credit David Cope and Shakespeare Central

Comments